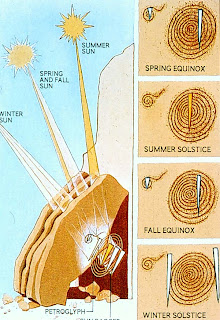

The Sun Dagger site, near the top of Fajada Butte, revealed the changing of the seasons to Anasazi astronomers a thousand years ago. Its secret was lost around 1250 AD, when the ancient people abandoned Chaco Canyon. Then in 1979, an artist was studying petroglyph art at Chaco when she noticed that a slender beam of sunlight passing between two rock monoliths bisected the center of a spiral-shaped symbol on the exact day of the summer solstice.

Returning time after time to continue her observations, she found that at the winter solstice the same "sun dagger" sliced through a smaller petroglyph nearby, and that two parallel daggers bracketed the larger spiral at the spring and fall equinoxes.

The discovery touched off a flurry of controversy. Scholarly experts scoffed. The sun, they pointed out, was not known to be represented by a spiral in any Anasazi petroglyph art. If the strange markings had actually served as a tool of prehistoric astronomy, they argued, would not the ancients have chosen a more appropriate symbol?

Further study revealed that the larger spiral's shape tracked an 18-1/2-year lunar cycle--an astronomical feat unheard of among North American Indians, though well known to the Toltecs of Mexico and the Maya before them. The sun dagger thus tended to confirm the prevailing academic hypothesis that Chaco Canyon was located at the end of a Toltec trade route, evidenced by such treasures as mother-of-pearl far from the sea and macaw feathers equally far from the jungle. The more the seemingly simple rock carvings were studied, the more mysterious they became.

Fajada Butte stands like a pyramid 480 feet above Chaco Canyon's broad, level floor. It used to be a quick, hard climb-steep and shadeless, crawling with rattlesnakes. But all that changed when a PBS television show about the sun dagger phenomenon, narrated by Robert Redford, captured viewers' imagination. In 1982, with tourists flocking to Chaco Canyon in record numbers, the National Park Service declared the butte and the area surrounding it off-limits to all but scientific researchers.

Yet there was no shortage of scientists trudging up the butte's steep trail with their heavy photographic equipment, then scrambling up the staircase of loose boulders to the site itself. In fact, more people began climbing Fajada Butte for officially sanctioned research purposes than had previously climbed it just because it was there.

Formerly faint, the trail wore deeper. Summer storms made a gutter of it. Disaster struck in 1989, when erosion of the clay and gravel around the base of the stone monoliths caused them to slip. As the slabs inched down the steep slope of the butte, the sun dagger vanished. Having unobtrusively marked the passage of seasons for many centuries; it lasted only ten years after its discovery before it was lost forever.

The loss of the sun dagger prompted the World Monuments Fund to add Chaco Canyon--now known as Chaco Culture National Historical Park--to its Most Endangered Monuments list in 1996. In a remote part of northwestern New Mexico's arid San Juan Basin, the canyon contains the ruins of the largest pre-Columbian "city" in what is now the United States.

The site's nine "great houses," the largest of which stood five stories high and had 650 dwelling rooms and 37 ceremonial kivas, along with some 3,500 smaller structures in and around the canyon, may have housed up to 10,000 people at a time. Chaco was the hub of a network of roads-at least 20 of them, each nearly 30 feet wide-that radiated in all directions for distances of up to 100 miles, suggesting that the site may have been a part-time home to pilgrims from other Anasazi settlements who came here for religious ceremonies, trade, or both.

Often, those who most treasure Chaco Canyon's silent mysteries unwittingly contribute to its slow destruction. As early as the mid-1970s, when an average of twelve people per week visited the site, environmentalists adopted the slogan "Don't pave the road to Chaco Canyon," and emblazoning it on T-shirts and bumper stickers. Though treacherous when it rains, the 30 miles of dusty washboard road into the monument remain unpaved to this day, but the Save Chaco Canyon campaign drew attention to the ruins and boosted the number of visitors annually from hundreds to thousands. In 1990, when spiritually aware pilgrims identified Chaco Canyon as one of the key sacred sites of the Harmonic Convergence, widespread publicity helped increase the number of visitors to nearly 20,000 a year, a rise that continues today. Looting has become a problem at outlying sites, and within the park visitors find themselves subject to ever more stringent backcountry hiking restrictions.

Besides human visitors, the World Monuments Fund reports, Chaco's ruins are threatened by natural phenomena: rains that seep into masonry joints; snow accumulations that melt and trickle down into walls, then freeze and expand, widening cracks; windstorms; livestock; even weeds. Protected for centuries by the windblown sand that covered most of the surviving stone walls, the ruins became vulnerable to erosion when archaeologists excavated them. Today, National Park Service officials report, the deterioration of the ruins far exceeds the government's financial ability to maintain them.

The World Monuments Fund recently received grants from American Express and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation sufficient to protect some, but not all, of the sites on their Endangered Monuments list. But on May 23, 1996, the World Monuments Fund announced its decision: Chaco Canyon was not selected in the first round of grants.

Undaunted, grassroots groups are organizing workshops and conferences to promote plans for Chaco Canyon's salvation. Public concern, all agree, is the key. It does not seem too much to hope that citizen activists can find the ways and means to preserve the vestiges of this once-great civilization while there is still time.

Found Here: http://www.angelfire.com/indie/anna_jones1/lost_dagger.html

No comments:

Post a Comment